Military history of New Zealand

| History of New Zealand |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| General topics |

| Prior to 1800 |

| 19th century |

| Stages of independence |

| World Wars |

| Post-war and contemporary history |

|

| See also |

|

|

The military history of New Zealand is an aspect of the history of New Zealand that spans several hundred years. When first settled by Māori almost a millennium ago, there was much land and resources, but war began to break out as the country's carrying capacity was approached. Initially being fought with close-range weapons of wood and stone, this continued on and off until Europeans arrived, bringing with them new weapons such as muskets. Colonisation by Britain led to the New Zealand Wars in the 19th century in which settler and imperial troops and their Māori allies fought against other Māori and a handful of Pākehā. In the first half of the 20th century, New Zealanders of all races fought alongside Britain in the Boer War and both World Wars. In the second half of the century and into this century the New Zealand Defence Force has provided token assistance to the United States in several conflicts. New Zealand has also contributed troops extensively to multilateral peacekeeping operations.

Māori warfare pre-1808

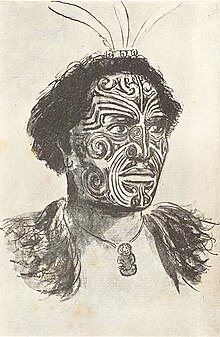

[edit]In Making Peoples James Belich argues that wars were probably uncommon in the few centuries immediately after the arrival of Māori in New Zealand in about 1280 CE.[1] Wars eventually broke out between tribal groups for practical reasons like population pressures, competition for land and natural resources, and the need to protect food supplies. The rise and development of fortified Māori villages, or "pā", in the 16th century suggests growing concerns from Māori tribes for defending valuable horticultural areas, with 98 per cent of pā situated in these areas. Several military campaigns were also fought for cultural reasons, often linked to the concepts of mana and utu, with some conflicts beginning because a tribal group wanted to increase tribal or personal mana, or a cultural requirement to make reprisals in response to insults, injury, or trespassing.[2]

War parties typically used stone or wood weapons designed for hand-to-hand combat. Warriors were often armed with a long-handled staff like a taiaha, and a shorter club like a patu. Warriors typically only wore a kilt and a tātua, although in some cases, cloaks were worn to shield themselves against spear thrusts.[3]

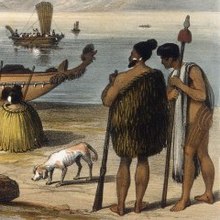

Wars were often fought through war parties called a taua, which can range from a small group to several hundred people. Larger war parties often travelled in a waka taua, or war party canoe. War parties would often employ deception to trick opposing tribes into letting their guard down or draw them out of a pā.[4] Battles typically took place in the summer months after tribes had completed their harvest. After the battle, the victors would enslave the prisoners of the defeated people, although in some cases, the prisoners would be killed and eaten. The consequences of the defeated people depended on the closeness between the two groups. In some cases, the victors would marry women from the defeated group, and the tribes would merge.[5] The largest battle prior to the introduction of muskets was the Battle of Hingakaka in 1807, which involved several thousand combatants.

Warfare on the Chatham Islands was nonexistent from the 16th century to the 19th century after the Moriori living on the island were able to forge a continuous period of peace. The continuous peace was established after a series of conflicts, when a local chief, Nunuku-whenua, declared an end to war, and a permanent restriction on murder and cannibalism.[2]

Early contact period

[edit]Musket Wars (1818–1830s)

[edit]The introduction of muskets in the early 19th century led to the Musket Wars, a series of battles and wars among Māori tribes from 1818 to 1840. The Musket Wars was the most geographically widespread conflict in New Zealand, affecting all parts of the North and South islands as well as the Chatham Islands.[6] Despite the conflict's name, muskets didn't fundamentally change tribal relations, with historians like Angela Ballara pointing out that many of the conflicts during the Musket Wars would have occurred regardless – albeit at a less destructive scale. The introduction of potatoes to New Zealand had a much greater effect on how wars were fought in the region.[7] The introduction of potatoes enabled more men to fight, as potatoes were an easier crop to harvest and provided more food per hectare than traditionally grown crops. The surplus in food stores also provided war parties the opportunity to travel greater distances to fight their wars. European ships also extended the reach war parties were able to travel.[6]

Although the introduction of muskets provided war parties with the opportunity to fight at a distance, there was no immediate change in how wars were conducted, with changes in weaponry and strategy taking place in phases.[6] However, it did transform agricultural practices, as economic production shifted to finance the acquisition of muskets from European traders until tribal armouries were filled. Strategies also changed as war parties adopted volley fire tactics, and "gunfighter pā" were developed in response to the use of muskets.[8]

Ngāpuhi were the first Māori tribes to use muskets in a tribal conflict. At the Battle of Moremonui around 1807–08, a Ngāti Whātua war party armed with traditional weapons successfully ambushed a Ngāpuhi war party armed with muskets. Although they were defeated, a Ngāpuhi rangatira, Hongi Hika, became convinced of the musket's shock value and worked to stockpile more muskets.[9] By 1818, Hongi had acquired enough muskets to lead a taua to raid villages along the Bay of Plenty.[10][9] Their campaign around the Bay of Plenty and a subsequent campaign in the Coromandel Peninsula in 1821 resulted in the capture of 4,000 slaves. Most of these slaves were put to work dressing flax to be traded for additional muskets.[9] In 1825, Hongi defeated Ngāti Whātua at Kaipara.[10] However, by the mid-1820s, Ngāpuhi dominance had begun to wane, as they did not have the infrastructure to maintain these large-scale campaigns and other tribes had begun to adapt to gunpowder warfare.[10] Hongi's death in 1827 hastened the end of large-scale tribal conflicts, as other Ngāpuhi rangatira unable to inspire the number of warriors Hongi.[9][10] Ngāpuhi were also weakened by an inter-hapū conflict, fought between northern and southern Ngāpuhi hapū over control of Kororāreka, an important centre for European trade.[10][11]

Nonetheless, Ngāpuhi's stockpiling of muskets and their subsequent military campaigns had altered the balance of power and prompted an arms race in the region, as tribes who felt threatened stockpiled their own muskets and launched their own campaigns to secure their territories.[12] Waikato Tainui launched several campaigns against tribes around Hawke's Bay and Taranaki in the mid-1820s to the 1830s, successfully securing their territory from northern incursion, and expelling Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Maru, and a large number of Ngāti Raukawa from Waikato.[13]

Ngāti Toa and their allies also embarked on several campaigns following their expulsion from the Waikato coast in 1821. Led by Te Rauparaha, Ngāti Toa migrated to the Kāpiti Coast, an area seen as desirable due to its proximity to European trade, and captured the Kāpiti Island from the Muaūpoko. The desirability of the location led to several skirmishes culminating in the battle of Waiorua in 1824, in which Ngāti Toa emerged victorious. Wanting to extend his trading strength, Te Rauparaha launched several campaigns against the tribes of the South Island and the Chatham Islands.[14] Campaigns to the Chatham Islands resulted in the Moriori genocide, where a population of about 2,000 was reduced to 101 by 1862.[15]

These conflicts began to subside in the 1830s, as tribal economies could no longer support the large-scale campaigns fought in the 1820s. Many tribes had also become well-armed, making quick and decisive battles less feasible. It is estimated that 18,000 to 20,000 civilians and combatants were killed during the conflict.[6][7] The Musket Wars saw tribal boundaries redrawn, which later became codified by the Māori Land Court, which determined that boundaries would be set as they were in 1840 when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed.[6]

Early British-Māori engagements

[edit]The Harriet Affair in 1834 was the first engagement fought between the Māori and the British. A British expedition was dispatched to Taranaki by the governor of New South Wales, Richard Bourke, at the request of John Guard, to rescue his wife Betty Guard and their two children following their kidnapping by local Māori of the Taranaki and Ngāti Ruanui iwi. The expedition was subsequently criticised for the use of excessive force against the Māori people in a British House of Commons report in 1835.[16][17]

Wairau Affray (1843)

[edit]

The Wairau Affray was an early engagement between Ngāti Toa and British settlers in Nelson and the New Zealand Company.[18] After the company refused to adhere to Ngāti Toa orders to halt the survey in lands that were not included in the company's purchases in 1839, Te Rauparaha moved into the area and burnt the surveyor's shelters. Sensing an opportunity, Nelson settlers ordered the arrest of Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata on charges of arson and sent an armed posse to arrest the two.[19]

The armed posse converged on Ngāti Toa party on 17 June 1843. Rising tensions between the two parties erupted into a skirmish that resulted in the death of nine settlers and two Māori. Four more settlers were killed during a disorganised retreat, and the remaining nine were captured and later executed.[19] The governor of New Zealand, Robert FitzRoy, resisted calls from settlers to bring those responsible for the posse's death to justice, and instead ruled that the New Zealand Company had provoked the Ngāti Toa by continuing the survey even though the Nelson settlers lacked any legitimate claims to land beyond Tasman Bay. The British Colonial Office approved of FitzRoy's response, as they did not want to incur the expense of a military campaign against Ngāti Toa.[20]

Colonial period

[edit]New Zealand Wars (1845–1872)

[edit]

The New Zealand Wars were a series of conflicts from 1845 to 1872, involving some iwi Māori and government forces, the latter including British and colonial troops and their Māori allies. The term New Zealand Wars is the most common name for the series of conflicts, a term used as early as 1920.[21][22] The Land Wars was another popular term for the series of conflicts, as the cause for these wars partially stemmed from land disputes. Other terms used since the late 1960s include the Anglo-Māori wars, the New Zealand civil wars, and the sovereignty wars. Māori names for the conflict include Ngā pakanga o Aotearoa (the New Zealand wars) and Te riri Pākehā (the white man’s anger).[21]

The first series of wars occurred in 1845, although the most sustained and widespread clashes occurred in the early 1860s between British imperial forces and the Māori King Movement.[21] By 1865, around 10,000 imperial soldiers had been deployed to New Zealand due to these sustained conflicts. However, by the end of 1864, in response to mounting British criticism over the colonial government's attitudes to the Māori and concerns over the cost of maintaining imperial troops, the colonial government implemented a "self-reliant" policy, aiming to replace imperial troops with local forces and Māori auxiliaries.[23] Most British troops departed New Zealand in 1866 and 1867, although the last British regiment did not depart until 1870.[23][24]

From 1864 to 1872, fighting ensued between colonial forces and their Māori allies against followers of Māori prophetic leaders.[21] As imperial forces scaled back their involvement, the burden of fighting on the Crown side increasingly fell on colonial troops and the kūpapa, many of whom were Māori who were committed to traditional Christianity and resisted the Kīngitangapā movement.[24]

It is estimated that over 500 British and colonial troops, along with approximately 250 kūpapa, died during the New Zealand Wars. On the opposing side, around 2,000 were estimated to have died. Māori that fought against the colonial government lost a substantial amount of land, with about 1,000,000 hectares (2,500,000 acres) of land confiscated by the Crown. Reparations for land confiscations did not begin until the 1990s.[25]

Flagstaff War (1845–1846)

[edit]The first conflict of the New Zealand Wars began after conflict broke out between Ngāpuhi led by Hōne Heke and colonial forces and Ngāpuhi led by Tāmati Wāka Nene. The cause for the conflict included Ngāpuhi economic concerns over the relocation of the Colony of New Zealand's capital to Auckland, and that the Crown had exceeded its authority. Heke and his supporters chopped down a flagstaff at Kororāreka to assert this point. However, other hapū of Ngāpuhi led by Wāka Nene sided with the British. In March 1845, Heke attacked the British forces at Kororāreka, which resulted in Pākehā evacuation of the settlement. The British military increased its presence in the colony after Kororāreka, dispatching the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot, and establishing a volunteer militia in Auckland. In April, a British force made up of regulars and volunteers left Auckland to reassert British sovereignty. After arriving at Kororāreka, British ships shelled nearby Māori settlements.[26]

The first major engagement between the British and Heke's supporters was the Battle of Puketutu, where British forces failed to storm Heke's pā stronghold. Heke withdrew to nearby Te Ahuahu after the battle to dislodge Ngāpuhi forces allied with the British from a pā, although was unsuccessful. In July, a 600-strong British force attacked a pā near Ōhaeawai although they later retreated. In January 1846, British forces shelled a new Māori fortification at Ruapekapeka. After the battle, Heke agreed to peace terms with Wāka Nene, ending the conflict.[26]

Hutt Valley and Whanganui campaigns (1846–1848)

[edit]

Land disputes between Māori and British settlers in Wellington led to tensions that occasionally broke out into violence. In March 1846, British troops clashed with Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Rangatahi in Hutt Valley, prompting Governor George Grey to declare martial law in Wellington.[27] Upon hearing that a taua was approaching Wellington, Grey extended martial law to Whanganui, and urged Te Āti Awa to intercept them, which they agreed to do. Grey then moved to arrest Te Rauparaha, whom he believed was responsible for the attacks in the Hutt Valley. In August, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Rangatahi and their allies withdrew from the area towards Pāuatahanui, although they were pursued by British troops and their Māori allies at the Battle of Battle Hill. The Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Rangatahi eventually reached Poroutawhao, after the British ended their pursuit.[27]

Hostilities erupted again after the British stationed troops in Whanganui, despite receiving warnings not to. Tensions were further exacerbated after Whanganui rangatira Hapurona Ngārangi was shot, and followers of Te Mamaku attacked an isolated farm in Matarawa valley and killed four residents. In May 1847, Whanganui Māori under Te Mamaku attacked a British settlement, although British troops and the town's settlers were able to withhold the attack by taking shelter in a stockade. In July, British forces moved out from the stockade to engage Te Mamaku's force in an inconclusive battle that resulted in Māori withdrawal. Grey pressed for peace and reached an agreement with Te Mamaku in February 1848.[27]

First Taranaki War (1860–1861)

[edit]The First Taranaki War originated from land disputes as settlers moved into Māori land. A young rangatira, Te Teira, offered 240 hectares (600 acres) of land near the mouth of the Waitara River, although he faced objections from a more senior rangatira, Wiremu Kīngi. Gore Browne, the governor of New Zealand, accepted the offer from Te Teira, with surveying of the land commencing by February 1860. After surveyors were interrupted by supporters of Wiremu Kīngi, British troops moved into the area and a blockhouse was built. In response, the Te Āti Awa erected a pā overlooking the British position. In March 1860, the British attacked the pā, leading to its subsequent abandonment by the Māori.[28]

A similar situation occurred 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south-west of New Plymouth, where a stockade was built by the British, and Ngāti Ruanui and their supporters built a pā overlooking the stockade. British forces eventually captured the pā at the Battle of Waireka, although some historians claim that the pā had already been abandoned by its defenders. The British subsequently attacked Te Āti Awa forces at Puketakauere pā in June 1860, although later withdrew to Waitara after sustaining heavy losses.[28]

After the British defeat at Puketakauere, Major-General Thomas Pratt took over command of the British force. In September, Pratt organised several raids against Te Āti Awa strongholds along the upper Waitara River and defeated a Ngāti Hāua war party in November. In January 1861, Pratt attacked Huirangi, causing Te Āti Awa to retreat upriver. Pratt continued to advance against Te Āti Awa, constructing a series of redoubts as he pushed further. After a night attack ended in disaster for the Māori, Te Āti Awa set up a defensive line of pā to protect the Pukerangiora pā. By February, the British dug trenches to close in on the pā and directed heavy artillery fire on the defensive line. However, the conflict ended a month later in March when a senior figure in the Māori King Movement, Wiremu Tamihana, brokered a truce.[28]

Invasion of the Waikato (1863–1864)

[edit]Despite the truce at Taranaki, the colonial government was keen to punish participants of the Māori King Movement who took part in the Taranaki War, and faced pressure from settlers to make the Waikato region suitable for their settlement. In 1862, work on the Great South Road began, allowing colonial forces to prepare for an invasion of the Waikato region. On 9 July 1863, a proclamation directed Waikato Māori living in government-controlled areas south of Auckland to take an oath of allegiance. Anorgwe proclamation was issued days later, warning those who resisted would forfeit their right to their lands.[29]

On 12 July, British forces crossed the border into lands belonging to the Māori King Movement and soon began to advance along the Waikato River. However, Māori attacks from behind the British front lines, and attacks against forward depots like Camerontown slowed the British advance. The Waikato Māori initially retreated to the pā at Meremere, although they later abandoned it after the British managed to land upriver to the rear of the pā.[29] After Meremere, the British shifted their attention to the Kīngitangapā at Rangiriri. The Battle of Rangiriri began on 20 November with a bombardment on the pā. The British assaulted the main redoubt of the pā, although were repulsed each time. However, the British seized the main line of retreat from the pā, preventing any further reinforcements from reaching the pā by nightfall. The pā was subsequently surrendered at dawn.[30]

The British proceeded to occupy Ngāruawāhia, prompting Kīngitanga forces to construct fortifications centred on Pāterangi. Realizing that his force could only take the fortifications with high casualties, the British commander, Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, opted instead to move around the southern flank of defences to reach food-producing villages like Rangiaowhia. Guided by local Māori friendly to the British, the force raided Rangiaowhia in February 1864, prompting the defenders at Pāterangi to withdraw and allow the British to occupy the pā unopposed. Kīngitanga forces attempted to reestablish their defensive lines along the Hairini ridge, but the British rushed troops to the area, forcing their further retreat.[30]

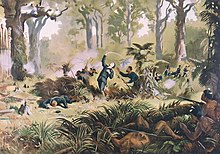

A Māori force led by Ngāti Maniapoto leader Rewi Maniapoto began to construct defensive earthworks at Ōrākau to stop the British. After spotting this construction effort, the British dispatched a force to oppose them, although their initial attacks were repulsed. However, as a British breakthrough into the pā seemed imminent, its defenders decided to abandon it on 2 April. The Battle of Ōrākau was the deadliest of the New Zealand Wars, with 17 British and up to 160 Māori killed during the engagement, most of the Māori deaths occurring during their withdrawal. After Ōrākau, the Kīngitanga withdrew behind another defensive line along the Pūniu River. Unwilling to pursue Kīngitanga forces further, and having achieved their goals in Waikato, the British force returned to Auckland.[30]

During the invasion, the British also launched a campaign in Tauranga to disrupt the flow of arms to Waikato. To resist further British encroachment, Rawiri Puhirake assembled a force of 250 Māori at Gate Pā. On 29 April, the British attacked the pā. However, the attack was repulsed, as its defenders were able to fire at the British through a network of underground trenches within the pā. The Māori abandoned Gate Pā the next day and moved to construct another pā at Te Ranga. However, they were caught off-guard and defeated by the British on June 21.[31]

Campaigns in Taranaki and East Coast (1864–1866)

[edit]By the mid-1860s, several Māori prophetic movements, like the Pai Mārire, emerged and imbued in their followers a renewed commitment to expel the Europeans. The first area impacted by these new religious movements was Taranaki. In April 1864, a small British force was attacked by Pai Mārire followers. In May 1864, a Pai Mārire taua moved to attack Whanganui villages, although they were intercepted at Moutoa Island by Whanganui Māori.[24]

In January 1865, Governor Grey dispatched a force to South Taranaki to confront 'hostile' Māori in South Taranaki. This force eventually encountered a pā of Weraroa, situated on a cliff-like embankment above Waitōtara. Although their commander, Lieutenant-General Cameron, preferred to isolate the pā, Grey disagreed, leading to the former's resignation. Major-General Trevor Chute replaced Cameron and departed Whanganui in December. From December to February, Chute's force conducted a route march aimed at destroying Taranaki Māori capacity for war by burning villages and livestock.[24]

Despite these early setbacks, Pai Mārire influence spread across the North Island. After several killings by Pai Mārire adherents, colonial troops were dispatched to Ōpōtiki on 8 September 1865, forcing Pai Mārire followers to retreat. Pai Mārire followers subsequently occupied Waerenga-a-hika (near Gisborne) until colonial forces besieged the area in November. The last Pai Mārire attacks in the area occurred in October 1866, when two groups of Pai Mārire followers were intercepted near Napier.[24]

Tītokowaru's War (1868–1869)

[edit]

From 1868 to 1869, Tītokowaru, a Ngā Ruahine Methodist preacher influenced by the Pai Mārire, led a campaign against the confiscation of Māori land. In June 1868, Tītokowaru’s forces attacked a small redoubt manned by the Armed Constabulary. In retaliation, the Armed Constabulary sent an expedition to attack the Tītokowaru’s village, Te Ngutu-o-te-manu, although the results were inconclusive. A second expedition was launched in September, although the force was defeated as it approached the village. After these defeats the Armed Constabulary abandoned the Waihī redoubt and withdrew to Waverley.[32]

In November 1868, Tītokowaru's forces repelled an attack by Crown forces and Māori under the leadership of Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui at Moturoa. Following the engagement, Tītokowaru moved to a pā near Nukumaru and began building massive earthworks. The Armed Constabulary prepared for an assault on the pā in February 1869, although it was found abandoned. The pā was abandoned after a major disagreement had arisen among its defenders and the decision was made to withdraw, effectively ending Tītokowaru’s campaign.[32]

Te Kooti's War (1868–1872)

[edit]

In July 1868, Te Kooti, the Ringatū founder, and 297 of his followers seized a schooner and forced its crew to sail them south of Poverty Bay, prompting colonial authorities to seek his capture. Te Kooti forces engaged with Crown forces several times, including at Ruakituri in August, and subsequently attacked Matawhero in November, killing 60 people including 30 Māori. Te Kooti then retreated to the hilltop fortress Ngātapa. On 5 December, the fortress was unsuccessfully attacked by the Armed Constabulary and Ngāti Porou with Wairoa allies led by Rāpata Wahawaha. The fortress was besieged again the next month. On the third day of the siege, Te Kooti's forces attempted a breakout, but they were detected and subsequently pursued by Crown forces.[33]

Te Kooti's remaining force escaped into Te Urewera, closely followed by Māori and Armed Constabulary units. Despite participating in multiple skirmishes and raids, Te Kooti managed to elude his pursuers in the ensuing months. Te Kooti eventually built a redoubt at Te Pōrere. On 4 October 1869, the Armed Constabulary and allied Māori attacked the redoubt in the Battle of Te Pōrere. Te Kooti was defeated but managed to elude his pursuers again. However, Te Kooti's followers were no longer able to defend a fixed position again, instead opting to move ahead of their pursuers. Te Kooti engaged with Crown forces at Te Hāpua on 1 September 1871 and at Mangaone on 4 February 1872. However, by 1872, Te Kooti's forces had dwindled in size. Te Kooti eventually took refuge in the Māori king’s stronghold of Tokangamutu, bringing his campaign to an end.[33]

Boer War (1899–1902)

[edit]

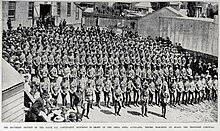

The Second Boer War was a conflict between the British Empire and the Boer republics in South Africa, a culmination of longstanding tensions between the two sides. On 28 September 1899, two weeks before the start of the conflict, the New Zealand House of Representatives approved the formation of a 200-man mounted rifle contingent for service in South Africa, in a show of colonial solidarity aimed at deterring the Boers from fighting.[34] The public responded enthusiastically to the war and calls for volunteers, with opposition to the conflict being minimal.[35][36] Premier Richard Seddon's goal for New Zealand to be the first colonial contingent in South Africa was realised when the first New Zealand contingent arrived in Cape Town on 23 November.[37] After its arrival, the First New Zealand Contingent was attached to Major-General John French's cavalry division.[38]

The first significant action and death of a New Zealand soldier occurred on 18 December at Jasfontein. In January 1900, a detachment of the British-New Zealander detachment repelled a Boer attack on the Slingersfontein farm.[38][39] The First Contingent continued its service with French's division, relieving the besieged town of Kimberley on 15 February. The British advance continued, and Bloemfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State, was occupied by March. Transvaal was annexed by the British on 25 October, after the decisive Battle of Paardeberg. At Paardeberg, the Second and Third New Zealand Contingents supported British forces under the command of Major-General Arthur Paget.[38]

After the events at Paardeberg, the conflict shifted into a protracted guerrilla warfare phase, with the Boer commandos operating on the veldt. To counter this, the British implemented a strategy to use mobile columns to track down the Boers, while many Boer families were placed in concentration camps and their livestock confiscated or culled.[39][40] The Six and Seventh New Zealand contingents were involved in these operations.[39] In 1901, the British adopted a new strategy to leave Boer women and children on their former farms to burden Boer men. Blockhouses linked by nearly barbed wire fences were erected across the countryside. This approach compelled Boers to surrender as guerillas were driven towards these blockhouses. On 23 February 1902, the last major engagement involving New Zealanders took place during one of these blockhouse drives.[40] The battle was the most costly action for New Zealand during the war with 90 men killed and 24 wounded.[39]

New Zealand sent 10 contingents, a total of approximately 6,500 men and 8,000 horses. The first five contingents embarked for South Africa in the first six months of the war. The last three contingents arrived in South Africa near the end of the conflict and saw limited action. The first two contingents were paid for by the New Zealand government, while the third and fourth contingents were paid for through community contributions. The subsequent six contingents were paid for by the British government.[41] A total of 230 New Zealanders died during the war, 71 were killed in action, 133 died from diseases, and 26 were killed in accidents.[39] The majority of New Zealanders who participated in the war were Pākehā. However, there was Māori support for the war, with Seddon and Māori leaders offering to send a Māori-manned contingent. However, the British government declined offers of Māori-manned contingents, as they believed 'native' troops should not participate in a "white man's war". However, some Māori individuals managed to enlist under anglicised names.[42][41] New Zealand women also played a significant role in funding the war, organising fundraisers like the Girls' and Ladies' Khaki Corps in lieu of government funding limitations.[36][41][43]

New Zealand's military institutions saw significant changes because of the war, with enlistment in the Volunteer Force increasing to 17,000 in 1901. The cadet system was also centralised under the Department of Education in 1902, with military drills being made compulsory several years later.[44]

World Wars and the interwar period

[edit]First World War (1914–1918)

[edit]On 4 August 1914, the British Empire, including New Zealand, entered the First World War as a part of the Entente powers. As a dominion of the Empire, the New Zealand government had control over what the country would provide to the imperial war effort.[45] Major General Alexander Godley served as the commander of the NZEF. Major General Alfred William Robin commanded New Zealand Military Forces at home throughout the conflict as commandant and was pivotal in ensuring the ongoing provision of reinforcements and support to the New Zealand military forces within New Zealand.[46]

The total number of troops and nurses from New Zealand military forces to serve overseas during the conflict was 103,000, from a population of just over a million.[47] About 42 per cent of men of military age served in the NZEF.[47][48] Approximately 32,000 soldiers sent overseas were conscripts, with New Zealand introducing military conscription in 1916.[48] The conflict was the first to see Māori and Pacific Islanders officially serve with the New Zealand Army in an overseas campaign. In total, 2,227 Māori and 500 Pacific islanders served with New Zealand forces.[49][50][51] In addition to New Zealand military forces, New Zealanders also served in British and Australian military units. About 700 New Zealanders served with the British Royal Flying Corps, while another 500 New Zealanders served in the Royal Navy.[48]

Throughout the war, 16,697 New Zealanders were killed and 41,317 were wounded, a 58 per cent casualty rate. A further thousand men died within five years of the war's end as a result of injuries sustained, and 507 died whilst training in New Zealand between 1914 and 1918.[47]

Pacific theatre

[edit]

The first wartime action undertaken by New Zealand was to carry out a request from the British to seize German Samoa. On 29 August, the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) landed in German Samoa unopposed, beginning the New Zealand occupation of German Samoa.[52]

Although most of the fighting occurred outside New Zealand, a German merchant raider, SMS Wolf, laid naval mines in New Zealand waters that resulted in the sinking of two ships and the death of 26 New Zealanders.[48]

Middle Eastern theatre

[edit]The first NZEF contingent to set sail for Europe left New Zealand on 16 October 1914, with plans to meet the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and set across the Indian Ocean together to join the British Expeditionary Force in France.[52] However, as they sailed the Indian Ocean, the Ottoman entry into the war changed the strategic situation and threatened an imperial lifeline, the Suez Canal. As a result, the NZEF and AIF disembarked in Egypt. During their time there, elements of the NZEF participated in the defence of the canal during an Ottoman raid in January–February 1915.[45]

As they were in the region, the NZEF and AIF were drawn into Allied plans to capture the Dardanelles Strait so naval forces could directly attack the Ottoman capital, Constantinople. After several Allied naval operations in the Dardanelles failed, Allied forces landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915. The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps landed at Anzac Cove and took responsibility for the northern sector of the battlefield. However, as Turkish defences made any significant Allied advance not possible, the fighting quickly transitioned into trench warfare. In August, Allied forces launched an offensive to break the stalemate, although it ended in failure. Allied troops were eventually evacuated from the peninsula in January 1916. During the Gallipoli campaign, 2,779 New Zealanders died.[53]

The Gallipoli campaign has impacted New Zealand's military culture since the war. The date of the landing at ANZAC Cove is commemorated in New Zealand as a public holiday, known as Anzac Day, to commemorate the country's war dead. The idea of the Anzac legend, which focused on the prowess of Australian and New Zealand soldiers, was also formed at Gallipoli.[54]

After Gallipoli, several New Zealand units remained engaged in further operations against the Ottomans. Following their evacuation from Gallipoli, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade joined Australian mounted units to form the ANZAC Mounted Division, and took part in the Sinai and Palestine campaign. During the Sinai and Palestine campaign, 543 New Zealanders died. A cruiser of the New Zealand Naval Forces, HMS Philomel, was also deployed to the Red Sea.[53]

Western Front

[edit]

By 1916, NZEF efforts were reoriented to the Western Front, with the New Zealand Division landing in France in April 1916, and its expeditionary headquarters established at Sling Camp in the Salisbury Plain Training Area.[48] In September 1916, the Division took part in the third major phase of the Battle of the Somme, assisting with the capture of Flers during the Battle of Flers–Courcelette.[55]

In 1917, units from New Zealand provided support in several campaigns, including the New Zealand Tunnelling Company during the Battle of Arras in April, and the New Zealand Division during the Battle of Messines in June. In late September, New Zealand forces were committed to support imperial forces at the Third Battle of Ypres and took part in two major attacks in October, the Battle of Broodseinde and First Battle of Passchendaele. The former was relatively successful for New Zealand forces while the latter engagement was a disaster that saw the highest one-day death toll suffered by New Zealand forces overseas.[55]

In March 1918, New Zealand forces took part in defending the British lines during Operation Michael, the campaign that began German Spring Offensive.[56] On 4 November, during the Allied Hundred Days Offensive, the New Zealand Division captured captured Le Quesnoy after an assault led by Lieutenant Leslie Cecil Lloyd Averill. The day was the Division's most successful on the Front, as they pushed east and advanced 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) and captured 2,000 German soldiers and 60 field guns.[57]

After the armistice of 11 November 1918, the New Zealand Division took part in the occupation of the German Rhineland until April 1919, when the Division was transferred back to the UK and subsequently disbanded. The process of repatriating NZEF troops from the UK back to New Zealand did not conclude until March 1920.[56]

Deployment to Fiji (1920)

[edit]In February 1920, New Zealand deployed a force of 56 soldiers to Fiji to support the civilian authorities during a period of civil unrest. Under the command of Major Edward Puttick, the small force deployed to Fiji on the government steamer Tutanekai and remained in Fiji until 18 April 1920. The force was the first peacetime deployment overseas by New Zealand military forces.[58]

Second World War (1939–1945)

[edit]In September 1939, the New Zealand government issued a declaration of war against Germany, backdated to the same moment the British declaration of war was made on 3 September.[59] Hostilities lasted until August 1945 with the capitulation of Japan. However, several New Zealand units were deployed to Japan as late as 1948, as a part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan.[60][61] Around 140,000 New Zealanders served during the war, with 11,928 New Zealanders killed during the conflict.[62]

Approximately 104,000 New Zealanders served with the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2NZEF), with the rest serving with other New Zealand or British military services.[62] Approximately 7,000 New Zealanders also served in the British Royal Navy and Fleet Air Arm. Another 12,000 New Zealanders served in the Royal Air Force. By the war's end, seven RAF "New Zealand" squadrons were formed, and more than 6,000 New Zealanders served with RAF Bomber Command.[63] In addition to Mediterranean and Pacific campaigns undertaken by New Zealand military forces, New Zealanders serving in the British Armed Forces also took part in the Battle of Britain, the Battle of the Atlantic, the Normandy landings, and the Western Allied invasion of Germany.[63][61]

Early naval operations

[edit]

The New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy (later renamed the Royal New Zealand Navy in 1941)[64] was among the earliest units to engage German forces, with HMS Achilles leaving for South American waters when the war began. In December 1939, Achilles helped destroy the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee at the Battle of the River Plate.[59] In 1940, after the fall of France, New Zealand aided French colonies in the Pacific aligned with Free France and dispatched the cruiser Achilles to French Polynesia.[65]

The presence of German merchant raiders in the South Pacific resulted in the sinking of New Zealand merchant vessels and casualties among New Zealand seamen clearing enemy mines in local waters during the war.[63]

Mediterranean and Middle East theatre

[edit]

The 2NZEF was formed with Major-General Bernard Freyberg assuming command of the force Training echelons of 2NZEF began to set sail for Egypt in January 1940.[59] The 2NZEF planned to reassemble in Egypt before continuing onto France, however, these plans fell through after the fall of France in June. The fall of France prompted the introduction of conscription in July 1940, to bolster the size of 2NZEF. A contingent from 2NZEF was dispatched to the United Kingdom, to be made available for the defence of the islands during the Battle of Britain. In late 1940, a few 2NZEF units participated Operation Compass, the British offensive against Italian Libya.[63]

In early 1941, a British force, which included the 2NZEF units sent to the United Kingdom, was dispatched to Egypt, uniting with other 2NZEF units that had assembled there. The 2nd New Zealand Division was then sent to Greece to bolster the country's defences in the lead-up to the German invasion of Greece. However, the subsequent German invasion forced the British force into retreat, and 2NZEF units were evacuated from the mainland by April 1941. The Division was then repositioned to Crete, with Major-General Freyberg taking command of all Allied forces on the island. On 20 May, German airborne units assaulted Crete. After an Allied counterattack failed, Allied positions became untenable and the island's defenders were evacuated. During the Greek and Crete campaigns, 982 New Zealanders were killed, and 4,006 were taken prisoner.[66]

From the rest of 1941 to 1943, the 2nd New Zealand Division took part in British Eighth Army's operations against Axis forces during the North African campaign. It was involved in Operation Crusader to relieve the siege of Tobruk in November 1941. From February to June 1942, the Division was stationed in Syria, a recently captured Vichy French territory. After a series of Axis counter-offensives in North Africa, the Division was recalled to Egypt and helped stop the Axis advance during the First Battle of El Alamein in July 1942, and the Second Battle of El Alamein in October–November. After the Axis defeat at El Alamein, Allied forces pursued them across North Africa to Tunisia, where Axis forces surrendered in May 1943. In total, 2,989 New Zealanders died, over 7,000 were wounded, and 4,041 were taken prisoner during the North African campaign.[67]

In October 1943, the 2nd New Zealand Division was deployed to Italy and took part in several engagements during the Italian campaign, including the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944, and the Operation Grapeshot in 1945.[61] In May 1945, the Division moved into Trieste to forestall its occupation by Yugoslav Partisans. A tense standoff between New Zealand and Yugoslav Partisans forces took place for several weeks before the latter's withdrew.[68] In total, 2,003 New Zealand soldiers died in the Italian campaign.[61]

Pacific War

[edit]

After the Japanese attacks on Allied territories in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, New Zealand sent an additional infantry brigade to reinforce Fiji. The question of recalling the 2nd New Zealand Division from the Mediterranean in light of the Japanese offensive was raised. However, as the Imperial Japanese Navy was present in the Indian Ocean, it was determined that the deployment of US forces to New Zealand would be a safer alternative. The first US soldiers arrived in June 1942, with 80,000 US soldiers having been posted in the country by the war's end.[69]

Although the Japanese had no plans to invade New Zealand, they did aim to cut the country off from Allied forces. However, these plans were thwarted in mid-1942, following the US naval victories at the Coral Sea and Midway. As a result of these victories, Japanese incursions into New Zealand waters were limited to submarines, which did no damage. New Zealand supported the American counter-offensive during the Guadalcanal campaign and placed its military forces at the disposal of the South Pacific Area command.[70]

New Zealand's military forces also partook in the Solomon Islands campaign. The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) dispatched the cruisers HMNZS Leander and Achilles successively to the Solomon Islands, although both were damaged by enemy action. By 1945, there were 8,000 airmen of the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) serving in the Solomons. The 3rd New Zealand Division was deployed to the Solomon Islands, although manpower issues in New Zealand eventually forced the Division's withdrawal and disbandment in 1944.[70]

During the latter stages of the Pacific War, RNZN cruisers Achilles and HMNZS Gambia were deployed to Japanese waters as a part of the British Pacific Fleet. After the surrender of Japan in 1945, New Zealand deployed both an air force squadron and an infantry brigade to Japan. This occupation force, known as J Force, consisted of 12,000 New Zealand personnel, and remained in Japan until 1948.[61]

Cold War era

[edit]The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the Eastern and Western blocs that lasted for nearly the entire latter half of the 20th century, from the end of the Second World War to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of the conflicts New Zealand was involved in during this period were the result of this tension and/or decolonisation.[71] New Zealand largely supported the Western Bloc throughout this period.[68]

New Zealand entered into several mutual defence treaties based in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, including the Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS Treaty) in 1951, and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in 1954. The former was a defence pact between Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, while the latter was a defence pact between New Zealand and several other countries with Southeast Asian territories.[72] New Zealand's participation in SEATO, as well as select conflicts, formed part of New Zealand's "forward defence" strategy, which aimed to contain the threat of the Eastern Bloc by preventing the spread of the communism in decolonised nations like Malaysia and Singapore.[73][74]

To support these commitments, compulsory military training was reimposed in 1949, following a referendum that strongly supported its reintroduction.[71] Conscripts were never sent to battle zones in this period, although many opted to continue their military careers and fight in Malaysia, Vietnam and other theatres of conflict.[60]

During the early periods of the Cold War, New Zealand provided an infantry division to help bolster British positions in the Middle East. However, these forces were eventually scaled back as New Zealand's defence strategy shifted from the Middle East to Southeast Asia.[72] From 1949 to 1951, a flight of No. 41 Squadron RNZAF was based in the colony of Singapore, and was attached to the RAF Far East Air Force, a unit that flew regular sorties to British Hong Kong.[75]

Korean War (1950–1953)

[edit]New Zealand was one of the first states to answer the United Nations Security Council's call for combat assistance at the outbreak of the Korean War. Two Royal New Zealand Navy frigates were dispatched to Japan and later took part in the Battle of Inchon in September 1950.[76] In January 1951, a contingent of New Zealand soldiers, known as Kayforce, landed in Korea as a part of British Commonwealth Forces Korea. Kayforce was made up of the 16th Field Regiment, Royal New Zealand Artillery and smaller ancillary units.[77]

In April 1951, during the Battle of Kapyong, the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade fought a successful defence against a Chinese division, with New Zealand gunners providing vital artillery support to Allied forces.[77] In late-1951, New Zealand gunners provided artillery support for Operation Commando and the Second Battle of Maryang-san. By the end of 1951, New Zealand had increased its commitment to the conflict, bolstering the number of troops in Kayforce in response to the establishment of the 1st Commonwealth Division.[78]

A stalemate between the United Nations Command and Chinese forces emerged in 1952. From this time to the end of the war, New Zealand gunners primarily supported infantry patrols, as well as provided defensive and routine harassing fire. RNZN sailors also continued to patrol the western coast of Korea, with six New Zealand frigates seeing service in that region by the end of the conflict. The fighting was brought to an end with the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement on 27 July 1953, although no final peace settlement was ever signed. As a result, New Zealand's military contribution to UN Command was reduced to one naval frigate attached to the Far East Fleet. In July 1957, Kayforce was finally withdrawn from Korea.[79]

In total, 4,700 men served in Kayforce, with another 1,300 serving on RNZN frigates in the area during New Zealand's seven-year involvement on the Korean peninsula. During those seven years, 45 soldiers died, with 33 of them occurring during the Korean War.[80]

Malaysia (1949–1966)

[edit]From 1949 to 1966, New Zealand military forces were deployed to Malaysia in support of Commonwealth forces. During that time, approximately 4,000 New Zealand soldiers served there, of whom 20 died. However, only three were the result of enemy action.[75]

Malayan Emergency (1949–1960)

[edit]The Malayan Emergency arose from the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) attempt to overthrow the colonial administration in China. Throughout the conflict, New Zealand supported Commonwealth efforts to defeat the communist insurgency.[75] From 1949 to 1955, New Zealand's involvement was limited to a select number of New Zealand Army officers and NCOs attached to other British units or the Fiji Infantry Regiment. By 1956, 40 New Zealanders served in the Fiji Infantry Regiment, including its commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Ronald Tinker. In addition to New Zealand Army troops, HMNZS Pukaki also took part in early naval operations as a part of the British Far East Fleet.[75]

In 1955, New Zealand increased its engagement in the conflict, after it decided to contribute to the Commonwealth Far East Strategic Reserve. In May 1955, No. 14 Squadron RNZAF began to carry out operational strike missions, while No. 41 Squadron RNZAF provided supply drops in support of anti-guerilla forces. A New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) squadron was deployed near the Perak and Kelantan border in 1956 and Negri Sembilan in 1957, eliminating local MNLA groups in those areas. In 1958, the New Zealand Regiment relieved the NZSAS squadron serving in Malaya and took part in counter-insurgency operations in Perak. By late 1959, most insurgents had retreated to southern Thailand, and the Emergency was officially terminated on 31 July 1960. However, New Zealand infantry were periodically deployed to the border as part of counterinsurgency measures until 1964.[75]

Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation (1964–1966)

[edit]From 1964 to 1966, New Zealand aided Malaysia during the Borneo confrontation with Indonesia, after a request for military aid was made by the United Kingdom in December 1963. The New Zealand government had initially refused the request to station troops in Borneo. However, the New Zealand military was drawn into the conflict, after Indonesian forces landed at Labis in September 1964, and the mouth of the Kesang River in October 1964. In addition to these units, No. 14 Squadron RNZAF was deployed to Singapore as a part of the Commonwealth's air power deterrent during the Confrontation.[81]

In February 1965, the New Zealand government approved the deployment of a Special Air Service detachment to Borneo, and two additional RNZN minesweepers to join HMNZS Taranaki in patrolling the Malacca Strait. Following the Indonesian coup d'état in October 1965, military activity by Indonesian insurgents in Borneo decreased dramatically. In August 1966, Malaysia and Indonesia signed a peace treaty to end hostilities. New Zealand units completed their withdrawal from Borneo in October 1966.[81]

Vietnam War (1965–1972)

[edit]

The Vietnam War was a conflict between communist North Vietnam and the US-backed South Vietnam from 1960 to 1975. New Zealand forces supported American war efforts from 1965 to 1975. The conflict was the first war New Zealand took part in which the United Kingdom was not a direct participant in. In total, over 3,000 New Zealand soldiers took part in the conflict. There were 37 men who died while on active service, while an additional 187 were injured.[82]

Despite its initial reluctance, the New Zealand government ultimately deployed combat units in May 1965, driven by a fear that non-participation would jeopardise the ANZUS alliance. After the Indonesian-Malaysian Confrontation ended, New Zealand faced renewed pressure from the US to expand its commitment, resulting in the dispatch of two additional infantry companies in 1967 and an NZSAS unit the next year. New Zealand's contributions peaked at 548 soldiers in 1968 and were grouped into the 1st Australian Task Force. The task force primarily patrolled Phuoc Tuy, although also took part in large-scale actions like the Battle of Long Tan.[82]

As American strategy shifted towards Vietnamisation, New Zealand sent army training teams to assist the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and withdrew its combat forces, completing the withdrawal of all its combat units from Vietnam by 1971. In 1972, the army training missions were also withdrawn from Vietnam.[82]

After Vietnam

[edit]Compulsory military training in New Zealand came to an end in 1973, shortly after the country withdrew its military forces from Vietnam.[83]

The end of the Vietnam War was a major turning point in New Zealand's strategic policy development, as its officials began to question New Zealand's commitment to its regional defence pacts, and to "forward defence" in Southeast Asia. These questions stemmed from growing disillusionment with American security policy and increased opposition to nuclear weapons in New Zealand.[82][84] New Zealand also ended its participation in SEATO after it dissolved in 1975.[85]

In 1987, the New Zealand nuclear-free zone was established, causing the US to formally suspend its security obligations to New Zealand, effectively isolating it from the ANZUS arrangements.[84] However, New Zealand maintained its commitment to the Five Power Defence Arrangements, and maintained a military presence in Singapore until 1989.[85]

Post-Cold War era

[edit]Government policies during the latter decade of the Cold War and the 1990s heavily impacted the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Cuts to New Zealand's defence spending, the suspension of ANZUS obligations from the United States, and the prioritization of the NZDF's focus on peacekeeping operations resulted in the disbandment of the RNZAF's combat wings and the mothballing of the RNZAF's Aermacchi MB-339 and Douglas A-4 Skyhawk in 2001.[86]

Gulf War and enforcement of sanctions (1990–1998)

[edit]In November 1990, several months after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the UN Security Council authorised the use of force to force Iraq to withdraw. The New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) contributed military personnel to the US-led UN coalition.

In September 1990, the tanker HMNZS Endeavour was deployed alongside the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) task force to assist with transportation.[87] On the 17 December 1990, New Zealand two C-130 Hercules transport aircraft of No.40 Squadron arrived at King Khalid airport. These aircraft delivered troops and freight such as ammunition, mail, and equipment. They conducted 157 sorties and were withdrawn on 4 April 1991.[88] On the 16 January 1991, 32 of the 1st New Zealand Army Medical Team were integrated with the US Sixth Fleet in Bahrain. They were later joined on the 21 January with a 20-strong tri-service medical team.[89] From February 1991, Six Skyhawks and 60 personnel of No.2 Squadron assisted RAN anti-aircraft exercises.[90] There were 119 NZDF personnel deployed in the Gulf War, made up of maintenance and admin staff, pilots, air-movements, guards, and medics.

After the war, New Zealand contributed to the United Nations Special Commission to ensure Iraqi compliance with UN sanctions. In October 1995 and May 1996, HMNZS Wellington and Canterbury were deployed to the Persian Gulf to enforce sanctions.[91] In 1998, the NZDF deployed two P-3 Orion aircraft and two NZSAS teams in addition to a naval team to Diego Garcia and Kuwait respectively, in support of Operation Desert Thunder, a build-up of coalition forces in the Persian Gulf following Iraqi non-compliance with UN inspection requirements.[92]

War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

[edit]

In November 2001, New Zealand announced it would provide military assistance to the US-led Operation Enduring Freedom. A Royal New Zealand Navy frigate and Royal New Zealand Air Force P-3 Orion were also deployed to the Persian Gulf in support of the operation. From 2003 to 2013, the NZDF deployed a 122-person Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) to Bamyan Province, to assist local authorities in maintaining security. The PRT also managed the New Zealand Aid Programme teams. Corporal Willie Apiata of the Special Air Service was awarded the first Victoria Cross for New Zealand while serving in Afghanistan in 2004.[93]

Other logistical, instructional, liaison, planning and policy personnel of the NZDF were also deployed to serve in the Afghan headquarters for International Security Assistance Force, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, and Combined Forces Command-Afghanistan.[93] NZDF support staff and New Zealand Special Air Service soldiers worked as a training and support element with the Afghan National Police Crisis Response Unit.[93] The NZDF confirmed that it planned to end its 20-year deployment in May 2021, with the withdrawal of six personnel from the Afghan National Army's Officer Academy and NATO's Resolute Support Mission Headquarters.[94] The RNZAF was briefly redeployed to Afghanistan near the end of the conflict in August 2021, to evacuate New Zealand and Australian nationals, as well as select Afghanistan nationals.[95] To support the evacuation, 80 NZDF personnel were deployed to the Middle East, while 19 were deployed to Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul.[96]

Over 3,500 New Zealanders took part in military operations and training missions in Afghanistan.[97] Ten New Zealand soldiers died while in Afghanistan, eight of which occurred in combat.[93] On 4 August 2010, Lieutenant Tim O'Donnell of the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment was killed, marking the first combat death of a New Zealand soldier since July 2000 in East Timor.[98][99]

Supporting US-led campaigns in the Middle East (2015–present)

[edit]In 2016, the New Zealand Defence Force deployed a number of staff officers to the Combined Air and Space Operations Center at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar to support the US-led intervention in Iraq against the Islamic State. The NZDF states that the support provided by its staff officers in Qatar were limited to non-combat missions, although a Stuff investigation contested the NZDF's non-combatant status, noting how coalition members of the CAOC are leveraged to "to facilitate superior airpower operations".[100]

In January 2024, six NZDF personnel were deployed to support Operation Prosperity Guardian, a US-led military operation in response to Houthi attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea. The six NZDF personnel provided "precision targeting" for coalition forces and were stationed at coalition bases within the region.[101] The NZDF's mandate to support Operation Prosperity Guardian ends on 31 January 2025.[102]

Peacekeeping and observer missions

[edit]United Nations missions

[edit]

New Zealand has provided military personnel and money to help fund United Nations peacekeeping activities. The first UN missions that New Zealand contributed personnel to were the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan in 1952.[60][103] Other UN missions NZDF personnel took part in included the United Nations Iran–Iraq Military Observer Group following the Iran-Iraq War in 1988.[104]

During the Somali Civil War, the NZDF formed the New Zealand Supply Contingent Somalia to provide personnel to the US-led UN Unified Task Force and its successor, United Nations Operation in Somalia II.[105][106][107][108] No. 42 Squadron RNZAF also provided personnel to support the missions in Somalia.[109] Somalia was the first deployment of New Zealand combat troops to a war zone since the Vietnam War.

In addition to military personnel, New Zealand Police personnel have also served in peacekeeping missions to Cyprus (1964–1967), Namibia (1989–1990), East Timor (1999–2001 and 2006–2012), and Afghanistan (2005).[103]

Former Yugoslavia (1992–2007)

[edit]New Zealand's commitment to the Balkan states commenced in 1992 with the deployment of five soldiers as UN Military Observers serving with the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR). In March 1994 to January 1996 New Zealand committed the first of Five Company Groups of mechanised infantry serving as part of British battalions. These were termed OP RADIAN. When this commitment was withdrawn New Zealand continued to commit 12 to 15 artillery and armoured soldiers to the British contingent, as well as three Staff Officers to the NATO Stabilisation Force (SFOR). As the mission evolved, the New Zealand contingent changed to a Liaison and Observation Team in the Bosnian town of Preijedor. The contribution was maintained through the handover of the NATO SFOR mission to the European Union EUFOR Althea on 2 December 2004. The LOT was withdrawn on 5 April 2007 but the three staff officers, the last in a continuous 15-year contribution to the peacekeeping effort in the former Yugoslavia, departed on 29 June 2007. One member was seriously wounded during this period.[110]

East Timor (1999–2003, 2006)

[edit]

Following East Timor's vote for independence in 1999, the Australian-led INTERFET (International Force East Timor) was deployed with the permission of the Indonesian Government in response to a complete breakdown in order. INTERFET was composed of contributions from 17 nations, about 9,900 in total. New Zealand's contribution in East Timor included SAS special forces, infantry battalion and helicopters, backed by RNZN warships and RNZAF transport.

INTERFET was replaced by a United Nations mission (UNTAET – United Nations Transitional Authority in East Timor) which sought to move East Timor toward elections and self-government and the troops came under the command of UNTAET in late 2000, which was in turn replaced by UNMISET in 2002. At its peak, the New Zealand Defence Force had 1,100 personnel in East Timor – New Zealand's largest overseas military deployment since the Korean War. Overall New Zealand's contribution saw just short of 4,000 New Zealanders serve in East Timor. In addition to their operations against militia, the New Zealand troops were also involved in construction of roads and schools, water supplies, training the nascent Timor Leste Defence Force (F-FDTL) and other infrastructural assistance. English lessons and medical aid were also provided. New Zealand Defence Force personnel were withdrawn in November 2002 leaving only a small training team for the F-FDTL. However, in May 2006 widespread fighting broke out in the Timorese capital of Dili as a result of a mass resignation of 591 soldiers and increasing tension between the F-FDTL and the East Timorese police (PNTL). A contingent of 120 troops were dispatched and provided security in Dili alongside soldiers and police from Australia, Malaysia and Portugal. Four New Zealand peacekeepers have been killed on operations in East Timor.

Other peacekeeping operations

[edit]Rhodesia (1979–1980)

[edit]

In 1979, New Zealand contributed a force of seventy-five officers and men to the Commonwealth Monitoring Force which was established to oversee the implementation of the agreement which had ended the Rhodesian War. Troops supervised the concentration of the guerrilla forces into sixteen Assembly Places during the period in which the cease fire was implemented and national elections held. Following the election the Commonwealth Monitoring Force began withdrawing from the newly independent and renamed Zimbabwe on 2 March 1980 with the final members of the force leaving on 16 March.

Multi-National Force and Observers (1982–present)

[edit]On ANZAC Day 1982, a small group of twenty six New Zealand soldiers arrived in the Sinai as New Zealand's commitment to the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO). This was to be the beginning of an ongoing commitment of New Zealand Peacekeepers to the Sinai region. The task of the MFO was initially to supervise the withdrawal of Israeli military units from Egyptian territory. A rotary wing of the Royal New Zealand Air Force also served until 1986. New Zealand increased its commitment to this Mission, which is now tri-service in nature, with a group of about two platoons of specialist servicemen and women serving a six-month Tour of Duty with the MFO.

Cambodia (1991–2005)

[edit]In 1992, New Zealand contributed 30 non-combatant engineers to the Mine Clearing Training Unit (MCTU) and 40 communications specialists. In late 1992, the RNZN tasked a 30 strong team with coastal patrols and aided Vietnamese refugees.[111]

Solomon Islands (2003–2013)

[edit]

New Zealand participated in the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI), which aimed to restore peace following the Solomon Islands civil war. RAMSI acted as an interim police force and has been successful in improving the country's overall security conditions, including brokering the surrender of a notorious warlord, Harold Keke. New Zealand contributed four helicopters and about 230 personnel consisting of infantry, engineers, medical and support staff. RAMSI was scaled down in July 2004, as stability had gradually been restored to the country. It was now primarily a police force. In 2007, New Zealand forces provided support relief in the aftermath of the 2 April 2007 Solomon Islands earthquake. The Mission ended in August 2013.[112]

Iraq (2003–present)

[edit]The New Zealand government opposed and officially condemned the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Despite this, the frigate HMNZS Te Kaha (F77) and an RNZAF P-3 Orion maritime surveillance aircraft were deployed to the Gulf, under US command.[113][114]

Following the invasion, later in 2003 New Zealand supplied a number of engineers and armed troops to the coalition effort. Task Group Rake, a Royal New Zealand Engineers group, joined Multi-National Division South East for one year under British Army command.[115] Diplomatic cables leaked in 2010 suggested New Zealand had only done so in order to keep valuable Oil for Food contracts.[116][117]

In accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1483 New Zealand also contributed a small engineering and support force to assist in post-war reconstruction and provision of humanitarian aid. The engineers returned home in October 2004, but liaison and staff officers remained in Iraq working with coalition forces. As of 2012, one military observer from New Zealand was serving as part of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq.[118]

On the 10th anniversary of the invasion, New Zealand journalist Jon Stephenson – who was in Baghdad when the war began – said New Zealand's contribution to the recovery effort had been "grossly overstated".[119]

Tonga (2006)

[edit]On 18 November 2006, a contingent of seventy-two New Zealand Defence Force personnel and additional New Zealand Police officers was deployed to Tonga at the Tongan Government's request to assist in the restoration of calm after an outbreak of violence in the nation's capital, Nukuʻalofa. They were joined by Australian soldiers and Australian Federal Police officers. Their main objective is to assist the Tongan forces in protecting Tonga's international airport in Nukuʻalofa. The personnel returned on 2 December.[120]

Antarctica

[edit]

New Zealand's armed forces have been involved in Antarctic research and exploration since the 1950s. The Air Force operated two Auster T7 and a Beaver in Antarctica in the late 1950s, the Austers somewhat unsuccessfully. The navy has escorted supply ships and conducted its own supply missions, provided weather monitoring and support for U.S. activities in the 'frozen continent', conducted scientific research, and helped build Scott Base. In 1964, 40 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force, was re-equipped with the C-130H Hercules and, the following year, commenced regular flights to and from the Antarctic. The army, and later the other two services, have provided cargo handlers. No. 5 Squadron has operated in the airspace over and near Scott Base to provide search and rescue standby and to drop mail and medical supplies to the people wintering over.

See also

[edit]- Early naval vessels of New Zealand

- History of the Royal New Zealand Navy

- List of New Zealand military personnel

- List of New Zealander Victoria Cross recipients

- Military history of Oceania

References

[edit]- ^ Lowe, David J. (2008). "Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and the impacts of volcanism on early Maori society: an update" (PDF). University of Waikato. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Story:Riri - traditional Māori warfare". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Story:Rākau Māori – Māori weapons and their uses". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Strategies and battle terms". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Strategies and battle terms". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Musket wars overview". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Overview - Musket Wars". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Acquisition and use of muskets". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Beginnings - Musket Wars". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Warfare from the north". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Outbreak of the 'Girls' War' at Kororāreka". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 16 February 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "The arms race- Musket Wars". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Waikato". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Ngāti Toa and allies". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ Bartrop, Paul R.; Totten, Samuel (2007). Dictionary of Genocide. ABC-CLIO. p. 290. ISBN 9780313346415.

- ^ "The Harriet affair – a frontier of chaos?". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 25 January 2008.

- ^ "The Harriet Affair". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010.

- ^ "The Wairau Incident". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Violence erupts - The Wairau Incident". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "The fallout from Wairau - The Wairau Incident". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "New Zealand wars overview". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ O'Malley 2019, p. 29.

- ^ a b Barber, Richard Ainslie. "British troops in New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government.

- ^ a b c d e "Pai Mārire, South Taranaki and Whanganui, 1864–1866". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Long-term impact". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Northern war, 1845–1846". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Wellington and Whanganui wars, 1846–1848". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "North Taranaki war, 1860–1861". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Waikato war: beginnings". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Waikato war: major battles". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Gate Pā, Tauranga". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Tītokowaru's war, 1868–1869". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Pursuit of Te Kooti, 1868–1872". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Origins of the conflict - South African 'Boer' War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Origins of the war - South African War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "The home front - South African 'Boer' War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "New Zealand's response - South African War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Key battles: 1899-1900 - South African 'Boer' War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "The troopers in South Africa - South African War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Guerrilla war: 1901-1902 - South African 'Boer' War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "New Zealand's contribution - South African War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Māori and the war - South African 'Boer' War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Object: Uniform, woman's – Collections Online". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "The legacy - South African War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Origins - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Phillip. "Alfred William Robin". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Mary Edmond-Paul (2008). Lighted windows: critical essays on Robin Hyde . Otago University Press. p. 77. ISBN 1-877372-58-7

- ^ a b c d e "Preparing for the European campaign - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Māori Units of the NZEF". Nzhistory.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 26 March 2019. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Māhina-Tuai 2012, pp. 140–141.

- ^ "Niuean war heroes marked". Western Leader. 21 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2023 – via Stuff.

- ^ a b "Initial response - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Gallipoli and the war against Turkey - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Impact of the war - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Western Front, 1916 to 1917 - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Western Front, 1918 - First World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "The liberation of Le Quesnoy". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ McGibbon, Ian C.; Goldstone, Paul (2000). The Oxford companion to New Zealand military history. Auckland, N.Z.: Oxford University Press. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0195583760. OCLC 44652805.

- ^ a b c "New Zealand's involvement - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Subritzky, Mike (1995). The Vietnam Scrapbook The Second ANZAC Adventure. Blenheim: Three Feathers. ISBN 0-9583484-0-5; Major M.R. Wicksteed RNZA NZ Army Public Relations pamphlet.

- ^ a b c d e "Final victory - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Overview - Second World War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "A more intense effort, 1940 - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Second World War - The Royal New Zealand Navy". nzhistor.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Defeat in France, 1940 - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Greece and Crete, 1941 - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "North Africa campaign - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Cold War beginnings, 1945 to 1948 - Cold War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Japan enters the war - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "American counter-offensive - Second World War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Cold War - Asian conflicts". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Beyond Europe, 1949 to 1955 - Cold War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "South-East Asia - The Cold War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "South-East Asia, 1955 to 1975 - Cold War". teara.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Malayan Emergency". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 4 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "The 'first' and 'second' Korean Wars - Korean War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Kayforce joins the conflict - Korean War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "The Commonwealth Division - Korean War". nzhistory.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2023.