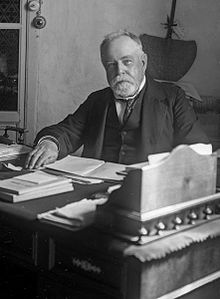

Pascual Cervera y Topete

Pascual Cervera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of the Navy of Spain | |

| In office 14 December 1892 – 23 March 1893 | |

| Monarch | Alfonso XIII of Spain |

| Regent | Maria Christina of Austria |

| Prime Minister | Práxedes Mateo Sagasta |

| Preceded by | José López Domínguez |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Pasquín de Juan |

| Chief of Staff of the Navy of Spain | |

| In office 7 November 1900 – 11 March 1901 | |

| Monarch | Alfonso XIII |

| Regent | Maria Christina of Austria |

| Prime Minister | Marcelo Azcárraga Práxedes Mateo Sagasta |

| Minister of the Navy | José Ramos Izquierdo Duke of Veragua |

| Preceded by | José María Pilón y Sterling |

| Succeeded by | Federico Estrán y Justo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 18, 1839 Medina-Sidonia, Cádiz province, Spain |

| Died | April 3, 1909 (aged 70) Puerto Real, Cádiz province, Spain |

| Resting place | Panteón de Marinos Ilustres, San Fernando, Cádiz province, Spain |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1858–1907 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Navy Staff Cuba Squadron Ministry of the Navy Cartagena harbor Battleship Pelayo Corvette Ferolana Corvette Santa Lucia Schooner Circe |

| Battles/wars | Ten Years' War Spanish–Moroccan War Spanish–Moro conflict

|

Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete (18 February 1839 – 3 April 1909) was a Spanish Navy officer and politician who served in a number of high-ranking positions within the Navy and fought in several wars during the 19th century. Having served in Morocco, the Philippines, and Cuba, he went on to serve as Minister of the Navy, Chief of Staff of the Navy, naval attaché in London, the captain of several warships, and most notably, commander of the Cuba Squadron during the Spanish–American War. Although he believed that the Spanish Navy was suffering from multiple problems and that there was no chance for victory over the United States Navy, Cervera took command of the squadron and fought in a last stand during the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, where he was decisively defeated.

Early life and service

[edit]Pascual Cervera y Topete was born in Medina-Sidonia in the province of Cadiz, the son of a Spanish Army officer who fought against French invasion of Spain during the Napoleonic Wars. Cervera entered the naval college at the age of thirteen and was later made a midshipman during his first voyage to Havana in 1858. He later made lieutenant junior grade at the age of 21[1][2] and spent time serving in both Cuba (during the early part of the Ten Years' War) and also Morocco (during the Spanish–Moroccan war).[3][4] Later, Cervera was deployed to the Spanish Philippines, where, under the command of Admiral Casto Méndez Núñez, in September 1864 he took part in the storming of Fort Pagalungan against the Moro rebels. During that action, he distinguished himself by capturing the enemy flag and was promoted to lieutenant for his service,[1] receiving a mention in the official report on the battle.[5] Afterwards, Cervera took part in expeditions mapping the hundreds of islands of the Philippine archipelago, which became useful to sailors navigating the area. In 1865 he returned to the Spanish homeland and got married.[1]

Due to the political instability that persisted in Spain since Napoleon's invasion, Cervera took part in putting down the Cantonal rebellion during one of the Carlist Wars. He later commanded the schooner Circe and the corvette Santa Lucia back in the Philippines, where Cervera again took part in operations against insurgents. In 1876 the Spanish captain was appointed as the Governor of Jolo, although he later contracted malaria because of the conditions there and barely survived, returning to Madrid to report on the conditions in the Philippines shortly after that at the request of Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo. Cánovas asked Cervera to take up the post of Minister of the Navy, but Cervera refused, saying that he preferred to be at sea rather than at a desk job. In 1879, he was given command of the training corvette Ferolana, where he remained until 1882, when he was transferred to oversee the Cartagena naval base. From 1885 to 1890, he served on the shipbuilding commission of the battleship Pelayo and became its first commander, but had to fight against the bureaucratic procedures of the Spanish Navy that caused delays in her construction.[1]

In the government

[edit]In May 1891, the Queen Regent María Cristina assigned Cervera to her court as her naval aide-de-camp. A year later the captain was assigned to oversee the construction of several cruisers for the Spanish Navy at the request of the Queen Regent. Around that time multiple politicians wanted Cervera to become the Minister of the Navy, but he continued to resist because he detested politics. Finally, in 1892, Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta asked the Queen Regent to compel him to accept the position of naval minister in his government. She did so, and Cervera reluctantly accepted, being promoted to Contraalmirante (rear admiral). But the newly promoted flag officer made the prime minister promise to not lower the naval budget in return, which Mateo accepted. However, it was not long before the prime minister broke that promise and so Cervera resigned from the position in 1892, but not before trying to make efforts to improve the Spanish Navy's efficiency. The rear admiral was appointed as the naval attaché in London shortly afterwards, where he witnessed the technical innovations being made by the British Royal Navy, a post he held until the situation in Cuba began escalating around 1896–97.[1][4][6]

Service in Cuba

[edit]

The admiral viewed the escalation of tensions between the kingdom and the United States with alarm, as he believed their defeat would be inevitable in a war because of the U.S. Navy's advancements between 1892 and 1896. Cervera thought that the Spanish were unprepared and did not possess enough ships to defend their colonies. Nonetheless, he accepted the posting of commander of the Cuban squadron on 20 October 1897 and immediately organized training exercises to prepare the crews, since the last time naval drills had been carried out was 1884 (during tensions with the German Empire over the Caroline Islands). Cervera sought to correct the numerous deficiencies in the fleet within a short time period, including lack of training and inadequate supplies. He continued to face difficulties from the naval ministry of Admiral Segismundo Bermejo, however. After the explosion aboard the American battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor in February 1898, the admiral sped back to Spain to speak to the government in person, but received orders from the Admiralty while at Cape Verde to take several ships back to Cuba and prepare for war, despite the severe problems in the fleet. Cervera returned to the Caribbean and slipped past American ships to enter the harbor Santiago de Cuba on May 19, despite several mishaps and having difficulties finding a port to refuel on coal, as most of the European countries with possessions in the Caribbean remained officially neutral.[1][4][6] His total force included the cruisers Infanta Maria Teresa, Vizcaya, Almirante Oquendo, and Cristóbal Colón, along with two destroyers.[7]

The U.S. remained unaware of the Spanish squadron's whereabouts for another several days, prior to it being discovered on May 28[8] or 29[9] at Santiago harbor by the Flying Squadron under Commodore Winfield Scott Schley. On May 31, the two sides exchanged fire, between the Cristóbal Colón and three American vessels (USS Iowa, Massachusetts, and New Orleans). After some time, Cervera ordered his squadron's cruiser to return to the harbor, with neither side having taken any damage. The rest of the North Atlantic Squadron under Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, operating in Cuban waters, did not arrive until June 1, and together the U.S. naval forces blockaded Cervera's squadron in Santiago. On June 2–3, the American commander decided to try to blockade the Spanish ships in the harbor by sinking a collier, the USS Merrimac, at the entrance. However, it came under fire from the defenders and was forced aground, at which point the Spanish admiral personally met with its American crewmen, who were taken prisoner.

"¡Bien, muy bien! ¡Sois unos valientes! ¡Os felicito!"

"Good, very good! You are brave! I congratulate you!"— Spanish admiral Pascual Cervera congratulating the American prisoners after their failed attempt, [10]

Cervera later sent his chief of staff under a flag of truce to give a note to Admiral Sampson informing him that the collier's crew was alive and safe. It was an act that impressed his American opponents and Sampson later noted that the affair "gave us a favorable impression of the Spanish officers."[11]

The fleet remained mostly inactive in harbor for the next month until July 2, when Ramón Blanco, the military governor of Cuba, gave orders for a sortie against the American blockade. Earlier, Admiral Cervera had argued with the authorities in Madrid against taking such an action, but Blanco settled the matter with his order. They formally departed on July 3.[1][12] The U.S. fleet sounded the alarm at 9:31 in the morning on July 3. The approaching Spanish ships, with Cervera's flagship Infanta Maria Teresa leading the way, opened fire and engaged the U.S. fleet. They headed west while remaining near the coastline.[13] The American battleships and cruisers pursued them as they made their way along the coast as the Spanish admiral's flagship sustained heavy damage from them. With their engines damaged, Cervera decided to ground the Infanta Maria Teresa, which they did at 10:15 am. Around 10:20, the Almirante Oquendo was forced out of action with heavy damage and grounded. The two destroyers, Plutón and Furor, put up a fight before also the former ran aground and the latter was sunk by 10:30 am.[14]

As the admiral's flagship raised a white flag on the beach, the remaining two cruisers – Vizcaya and Colón – were pursued, with the former being destroyed around 11:00 while the latter made it fifty miles from Santiago before being grounded on a beach. After that, the American ships began rescue operations for the Spanish sailors of the destroyed squadron, and among those captured from the wreck of the Infanta Maria Teresa was Admiral Cervera.[15] That afternoon, he made it onto the USS Iowa, where he and the other Spanish officers met with Captain Robley D. Evans and formally surrendered to them.[16] Afterwards, Cervera and the rest of the captured prisoners were sent to Annapolis, where they were free to roam the U.S. Naval Academy and were greeted with cheers by Americans. The New York Times reported that he appeared to be "much affected by the genuineness and spontaneity of the feeling manifested."[17] On August 20, he was offered freedom by the U.S. government on the condition that he would not take up arms against the United States, but he refused, saying that accepting conditional freedom was illegal by Spanish law, and did not return to Spain until September 1898. He gained popularity among both the Spanish and American public in the years after the war.[1]

Later life

[edit]In February 1901, Cervera was promoted to Vizealmirante (vice admiral) and in December 1902 became the Chief of Staff of the Navy. In May of the following year, King Alfonso XIII of Spain named him a senator of the kingdom for life. By 1906, his health was failing and Cervera was reassigned to manage the naval district of Ferrol before retiring the next year. He died on 3 April 1909.[1]

Personal life

[edit]Admiral Cervera was married and had several children, but he lived his private life with a rigid schedule.[1] One of his sons was also in the Spanish Navy and served with his father at Santiago.[18]

Cervera also spoke fluent English.[4]

Recognition

[edit]Admiral Cervera continued to be a popular figure in the years following his death, to the point that even the Spanish Navy acknowledged him as a symbol of patriotism by naming a light cruiser after him.[19]

Awards

[edit] Order of Isabella the Catholic

Order of Isabella the Catholic Royal and Military Order of Saint Hermenegild

Royal and Military Order of Saint Hermenegild Naval Merit Grand Cross

Naval Merit Grand Cross Naval Merit Cross with white badge

Naval Merit Cross with white badge Naval Merit Cross with red badge

Naval Merit Cross with red badge

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Manuel Cervera and Wayne Lydick. Admiral D. Pascual Cervera. Spanish–American War Centennial Website. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 86–87

- ^ Pascual Cervera y Topete Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Sariego, William (November 2015). Honor in Defeat. Avalanche Press. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Davis (1903), p. 162

- ^ a b Dyal (1996), pp. 68–71

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 87–88

- ^ Nofi (1996), p. 89

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 109–110

- ^ Biography of Pascual Cervera Todoavante (in spanish)

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 115–117

- ^ Leeke (2009), p. 125

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 130–132

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 134–137

- ^ Leeke (2009), pp. 138–142

- ^ Leeke (2009), p. 145

- ^ Leeke (2009), p. 148

- ^ Leeke (2009), p. 120

- ^ "Almirante Cervera" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 May 2000. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ a b Garcia, Tamara (2 May 2014). El testamento de Pascual Cervera y Topete. (in Spanish). Diario de Cadiz. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Davis, George W. (1903). Annual Report of Military Governor in the Philippine Islands. 1899–1902/03. Manila: Manila P.I.

- Dyal, Donald H. (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War. Greenwood. ISBN 0313288526.

- Leeke, Jim (2009). Manila and Santiago: The New Steel Navy in the Spanish–American War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1591144649.

- Nofi, Albert A. (1996). The Spanish–American War, 1898. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Books. ISBN 0-938289-57-8. OCLC 33970678.

Further reading

[edit]- Concas y Palau, Victor M. (1900). The Squadron of Admiral Cervera. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence.

External links

[edit]- 1839 births

- 1909 deaths

- Knights of the Legion of Honour

- People from La Janda

- Recipients of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Recipients of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Hermenegild

- Grand Crosses of Naval Merit

- Spanish admirals

- Spanish military personnel of the Spanish–American War

- Spanish–American War prisoners of war held by the United States

- Spanish prisoners of war